A Closer Look at the Collecting Strategies, Fiscal and Public Benefits of Opening Private Collections to the Public.

by Cat Weaver

Private collections that attract negative press have certainly set the dogs a-barkin. This is in part because the rules that identify who is or is not a museum, or what sorts of institutions deserve tax-exempt status are unclear. So stories that cover private collectors who take their collections public are often drenched in worries and cynicism. This is troubling since there are genuinely hefty social advantages to having private art in the public eye. Eager to see the bright side, galleryIntell took some of the most aired controversies and examined them with an eye toward the fair and balanced.

The Issues:

Competition with established institutions:

As we saw in Part 1 of this article, non-profits and publicly funded museums have found themselves in losing competition with individual collectors. The old institutions tend to get outbid at the major auctions, and … outclassed. ArtNet, for instance, has paraphrased “tycoon and art collector Budi Tek” who boasted about “haggling with dealers on prices by promising to build dedicated spaces for museum-scale artworks, such as the glass house he’s constructing for Maurizio Cattalan’s live olive tree.”

There are two other contributors of tensions between private and public art spaces. As the number of the super-rich collectors increases, art market prices escalate and that inflation, of course, grants advantages to extremely wealthy private collectors who have the financial capacity to allocate $20 – $40 million or more to a single artwork. The other possible culprit is the changes to the tax code. Some experts have suggested that changes curtailing donations to charitable institutions are to blame for the explosion of private museums and also for the unfair advantage they have over public ones because they drive potential donors away from giving and toward setting up for themselves.

How big is the problem?

Well, we saw that Jeffrey Deitch for instance, complained that “megacollectors pose a bigger threat to LA MOCA than do even the top galleries, many of which are known for producing museum-quality shows.” But did he really mean that his museum was in stiff competition for important acquisitions and that this was negatively impacting attendance?

We spoke to Juan Roselione -Valadez director of the Rubell Family Collection in Miami, FL who appeared to think that Mr. Deitch was, perhaps, overstating the case a bit.

Pointing out that the excitement generated by one museum feeds into the excitement that will go on to inspire attendance at others, Valadez hinted that the impact of one collection works symbiotically, not competitively, with the others. He also stated that public museums have the advantage of being free to “borrow from all over the world” whereas private collections, for the most part, could only show what they own. Albeit, as these private museums gain in prominence and recognition they are likely to form their own loan programs with other private and public institutions and thus expand their inventory.

As far as snatching up the picks of the litter, Valadez says “A museum can wait… they can take their time and choose art with proven historical impact. But we have to move quickly, acquiring new works – works that, frankly, the public museums may not want at the moment…”

Valadez is referring here to one of the important differences between public and private museums: public museums tend to acquire artists after their reputations and careers have been validated through solo shows, a strong market, and solid auction results. The Rubell Family Collection, and other private collections, on the other hand, tends to acquire artist’s works before they have the market’s imprimatur. “We have a group of Murakami’s (above) we acquired in 1999, and Richard Prince works acquired in 1979 and Jeff Koons acquired in 1980,” Valadez says. What’s notable was that these were purchased in “real time”, when the artists were not yet blue chip. There is also the question of how long it takes for a museum to make an acquisition decision vs. a private institution that has fewer voters on the acquisition board and more focus on the overall acquisition strategy.

Valadez is referring here to one of the important differences between public and private museums: public museums tend to acquire artists after their reputations and careers have been validated through solo shows, a strong market, and solid auction results. The Rubell Family Collection, and other private collections, on the other hand, tends to acquire artist’s works before they have the market’s imprimatur. “We have a group of Murakami’s (above) we acquired in 1999, and Richard Prince works acquired in 1979 and Jeff Koons acquired in 1980,” Valadez says. What’s notable was that these were purchased in “real time”, when the artists were not yet blue chip. There is also the question of how long it takes for a museum to make an acquisition decision vs. a private institution that has fewer voters on the acquisition board and more focus on the overall acquisition strategy.

Redundancy:

So many of the larger, more media-covered private museums and collections seem to focus on the same blue-chip, canon-sanctioned, contemporary art, or modern masters, leaving us to wonder: are they redundant?

The answer, as one may expect, differs by individual collections and the cities they are located in. Individual collectors can be more experimental, in acquisitions, and in exhibitions, formats, programs, etc. So, although a quick trot through any collection of contemporary art might leave the impression that it’s a lot of “same ‘ol-same ‘ol,” a more studied examination might yield some interesting insights. As an example, Valadez pointed to the RFCs displays which attempt to show artists’ works in context, often grouping several pieces by the same artist and taking into account career and art historical perspective. “We tend to avoid the menagerie. We prefer to show artists in context with a full view of their practice.”

Aside from the more traditional museums, the increase in private collections that make the public move has brought with it some very specialized collections – some more quirky than others. There is, for instance, Pasadena’s Bunny Museum which invites you to “hop on over,” and The Patent Model Museum in Cazenovia, New York, which boasts “the largest privately-owned collection of United States patent models in the world.”

It could be that as it becomes common for collectors to set up shop, these less hedge-strategic/more passion-driven will offer varied local flavor and cultural insights. Like a wiki forum, there is a rogue aspect to be explored and appreciated as individual input increases and supplements the traditional art historical POV.

How to have your cake and eat it too:

Headlines like “A Family’s Billions, Artfully Sheltered” in a 2011 issue of the New York Times, highlight the reasons that most people immediately flinch when big money is mixed with public service: it is easy to play the system if you have the money and the resources to do so — and if you are good at it, well, perhaps you build a philanthropic empire. To quote the article about Ronald Lauder’s private Neue Gallery, “By donating his art to his private foundation, Mr. Lauder has qualified for deductions worth tens of millions of dollars in federal income taxes over the years, savings that helped defray the hundreds of millions he has spent creating one of New York City’s cultural gems.”

Headlines like “A Family’s Billions, Artfully Sheltered” in a 2011 issue of the New York Times, highlight the reasons that most people immediately flinch when big money is mixed with public service: it is easy to play the system if you have the money and the resources to do so — and if you are good at it, well, perhaps you build a philanthropic empire. To quote the article about Ronald Lauder’s private Neue Gallery, “By donating his art to his private foundation, Mr. Lauder has qualified for deductions worth tens of millions of dollars in federal income taxes over the years, savings that helped defray the hundreds of millions he has spent creating one of New York City’s cultural gems.”

And now about that “layered cake of benefits” we talked about in the beginning. How does a smart, financially informed collector position him/herself to reap the most benefit? Simple. Create a foundation to take ownership of your art and the growth of your collection’s value will give new meaning to art appreciation. Foundations pay no capital gains, and no sales tax in most states. On top of that, the “donation” is, in itself, tax deductible. Once the foundation is set up, your collection can be maintained and housed at the cost of a few tax-deductible cash donations. Furthermore, your heirs will appreciate the fact that there is no estate tax to pay when you slip away.

To be fair, alarms may go off, but the balance of social benefit (in the form of culture and charitable giving) to social detriment (in the form of tax sheltering) is difficult to measure. Depending on the philanthropic outreach, the way a collection is used for public enlightenment and shared with museums across the country, and the great wealth of gifts handed over to museums, the tax situation may just be a win/win. The public conversation is on-going with laws governing charitable giving constantly evolving to prevent what is called “self service.”

Access:

Ideally, art collectors who establish museums and public programs, generate a cycle of mutual support with their neighborhoods, cities, and cultural centers. They get to see their acquisitions installed in one location, and visitors get to experience well cared for, custom-displayed artworks that they would otherwise never see. But what can they see, and when can they see it? There has been some concern about the way that these collections are allowed to set up viewing hours that vary in eccentricity. Supposedly, to meet requirements for tax exemption, they must maintain access to the public; but the controls, requirements, and restrictions, and the hours that are chosen, are oft-times prohibitive.

As of January, The Warehouse, an exhibition space developed together by the Rachofskys and the Faulkeners, will be available only for guided educational tours, granted to groups of ten or more and scheduled three weeks in advance. At the end of the day a private collection, is a collector’s or a foundation’s private space and rules are drawn to best accommodate the interests of the collection and its program.

This article ©galleryIntell 2013.

Note: The article from Monday July 1st has been revised to reflect the different sorts of institutions and programs that are used to bring private collections into the public forum.

Featured artwork:

Takashi Murakami DOB in The Strange Forest, 1999. FRP, resin, fiberglass, acrylic and iron. 120 x 120 x 50 in. Rubell Family Collection. Acquired in 1999

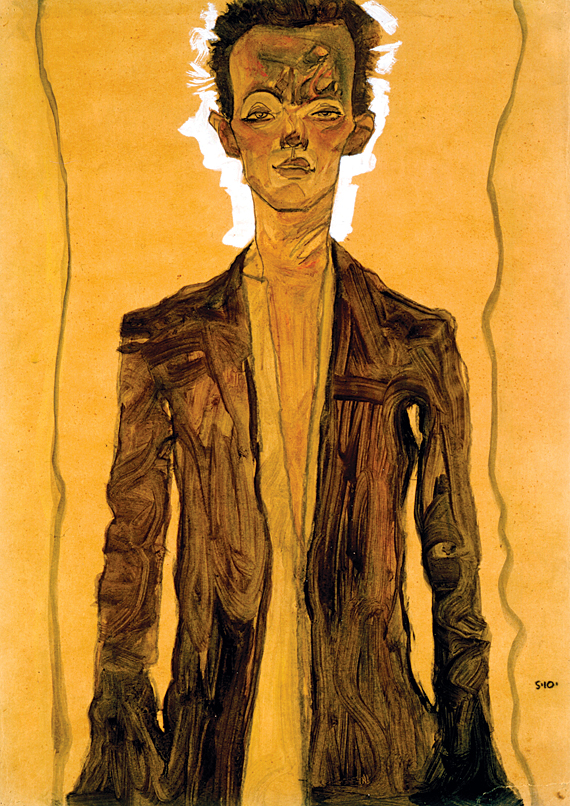

Egon Schiele (1890–1918), Self-Portrait in Brown Coat, 1910. Watercolor, gouache, and black crayon on paper. Private collection, New York.